"Words matter. Artists love to trot out the tired line, 'My work speaks for itself,' but the truth is, our work doesn’t speak for itself" - Austin Kleon

Masterpiece in the Subway

In the book The Tipping Point by Malcom Gladwell, one of Gladwell's observations is humans act very differently toward the same inputs in different situations.

In other words, context matters. Context tells a story and, to a large degree, human reactions are influenced by the story of context.

Here's a dramatic example of how context matters: A few years ago an experiment was staged with world-class violinist, Joshua Bell, who, fresh from a performance at the Library of Congress with the Boston Symphony, panhandled for free during the morning rush at a Washington Metro station. Of the thousand-odd passersby, only a few stopped, or even paused, to listen.

Watch a video of Bell's fascinating performance:

What happens when we take one of the world's finest musicians, who normally makes over $1,000 per minute and put him in the "wrong" context of a subway panhandler?

The story of this particular context gives people a strong clue that, “this musician is a panhandler.” And, so, the masses simply see him as a panhandler, or, they are simply too busy with their commute to notice him. Most don't recognize the artistic gift for what it truly is. Because it's in the wrong context.

The "right" or "wrong" context is just a type of story. And stories matter. Even the stories we tell ourselves about virtuosos and panhandlers.

The Stories of Context

Instead of a violinist, let's consider an art forger.

Say we take a forged painting out of the garage and put it in the worlds finest museums and galleries, and let the critics rave about it, what will the masses do? They'll see that forgery as "important" But, again, it's only because of the context. And the story implied by that context.

I recall a few years ago, someone found a bunch of suspected Jackson Pollock paintings in a garage and experts spent weeks subjecting the canvases to all kinds of scrutiny to determine if they were real. Were they painted by Pollock himself? Or were they some house painter's drop cloth?

The entire value of those paintings depended upon the story told by those experts: If they were authenticated Pollocks - they were worth millions. If they were not Pollocks - they were worthless trash.

Consider the following excerpt from Austin Kleon's book Show Your Work:

Art forgery is a strange phenomenon. “You might think that the pleasure you get from a painting depends on its color and its shape and its pattern,” says psychology professor Paul Bloom. “And if that’s right, it shouldn’t matter whether it’s an original or a forgery.” But our brains don’t work that way. “When shown an object, or given a food, or shown a face, people’s assessment of it - how much they like it, how valuable it is - is deeply affected by what you tell them about it.”

Trash in the Museum

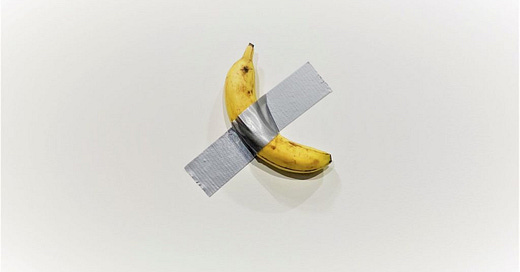

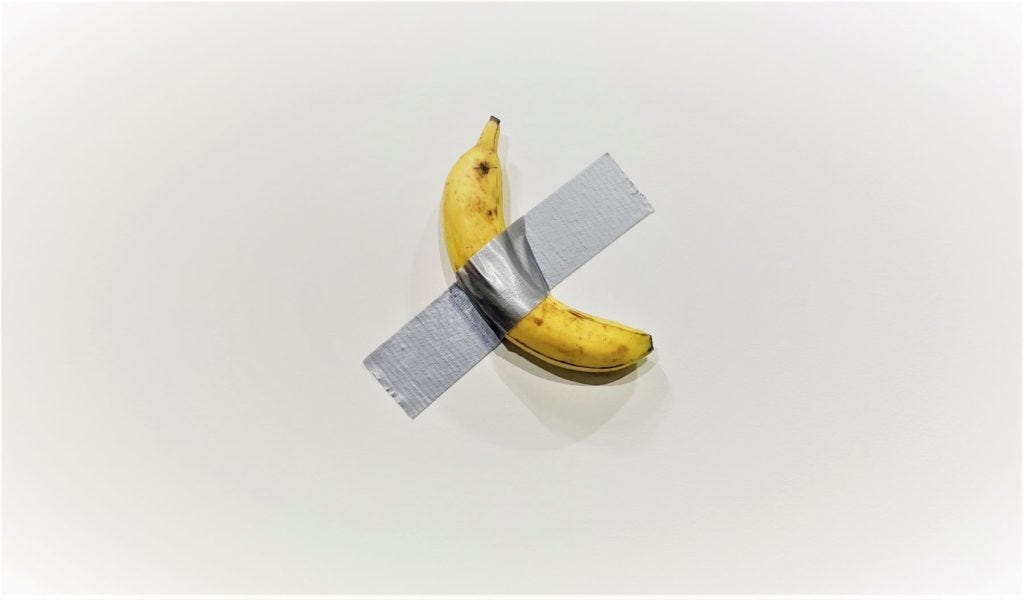

Stories matter so much that, if you tell the right story, in the right context, you can turn "trash", a browning banana duct-taped to a wall, into "art" that sells for $120,000 or more:

"An art piece of a banana duct-taped to a wall, which captured a lot of buzz in the past week, has reportedly been taken down at the Art Basel show in Miami Beach. The controversy-stirring artwork first sold for $120,000, and then was sold two more times for $120,000 to $150,000" reported The Times.

In their book, Significant Objects, Joshua Glenn and Rob Walker actually test the power of stories that allowed that banana to sell for six figures.

Here is their hypothesis:

"Stories are such a powerful driver of emotional value that their effect on any given object’s subjective value can actually be measured objectively."

Here is how they tested it: First, they went out to thrift stores, flea markets, and yard sales and bought a bunch of “insignificant” objects for an average of $1.25 an object. Then, they hired a bunch of writers, both famous and not-so-famous, to invent a story “that attributed significance” to each object. Finally, they listed each object on eBay, using the invented stories as the object’s description, and whatever they had originally paid for the object as the auction’s starting price. By the end of the experiment, they had sold $128.74 worth of trinkets for $3,612.51. They made a profit of over 2,700% of their investment simply by crafting the right stories.

Learn to Look Past the Context and the Story

First, if you can, in your own mind, move beyond context, you can learn to see reality as it is.

So next time you see a panhandler, listen carefully - picture him playing with a symphony. And next time you see the latest "masterpiece" in a museum - picture it hanging in your garage or even imagine that YOU had painted it. Ask yourself, would you be happy letting it out of your studio? Take the artwork OUT of context for a moment and judge on the merits of the work itself. This is a great skill to develop for finding "diamonds in the rough."

Secondly, and more importantly from from a marketing perspective, think carefully about the stories, both verbal and non-verbal, you're telling the world about your own art.

Paraphrasing professor Bloom's observation: people's assessment of your art, how much they like it, how valuable they think it is - will be deeply affected by what you tell them about it.

In what context are you presenting your work? What stories are you telling people about your art?

Think through those questions carefully. As you've seen, they're important.

I want to save this reminder, Clint, I remember the anecdotes and love seeing the lesson distilled from them.

I want to see the creators and their things of beauty, invested with a piece of their mortality, for their beauty, just as I want me and mine to be seen for what it has, by those looking for it, whether they realize it or not at the time.

This is great, thanks Clint. Actually gave me a lot to chew on.

I'm glad of your approach to the DC metro thing. I normally hate that example because people lean on it as an example of how uneducated and pedestrian people are: "Oh, they're so busy going to work they don't recognize top art!"

Naw man, I recognize great buskers in the subways all the time. But I'm going to work. It's the wrong venue to deliver this to me.

In video, this is why Vimeo is different than YouTube (is different than TikTok). "Short film" vs "video content" vs "social media video".